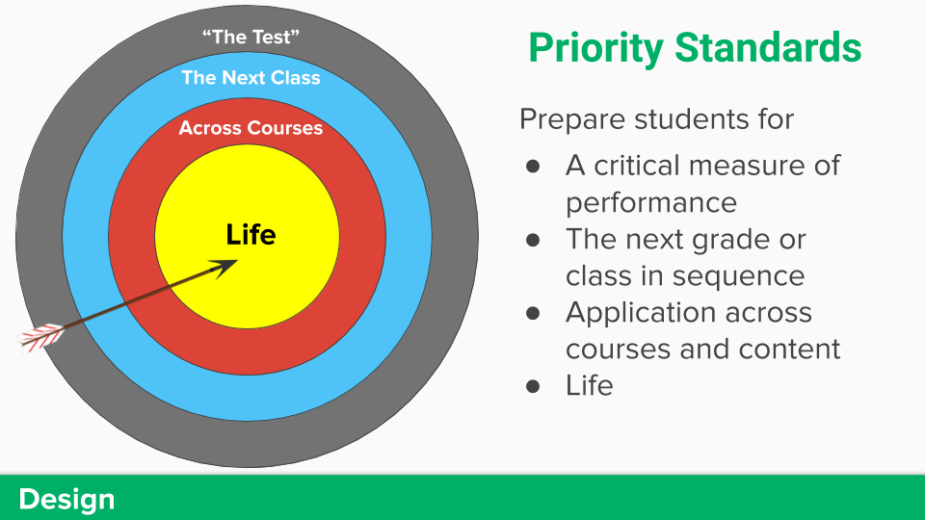

This four-part series on Deeper Assessment began with a high-level overview of using backwards design to decide what we really want students to know and do. Prioritizing learning outcomes is a common first step in designing a guaranteed and viable curriculum that prepares students beyond “the test.” Prioritizing standards helps determine vertical scope to prepare students for future courses in their sequence as well as to develop transferable skills across courses and subject areas. Ultimately, the highest priority standards help prepare students for “life,” whatever that may look like now, a month from now, or years from now.

The session started with a short clip from Ted Dintersmith’s Most Likely to Succeed of Linda Darling-Hammond sharing research on how fleeting inert knowledge is. Inert knowledge is information we memorize and repeat but never really use, and we lose about 90% of all inert knowledge we are exposed to. The clip from Dintersmith’s Innovation Playlist reports findings from a study conducted at the Lawrenceville Academy in New Jersey, where over two years, students were re-tested in the fall on their final science exams. Average scores went from a B+ to an F. Most students failed their exams after just three months. Moderator Julie Foss asked the 20+ participants in the session whether they might expect these same outcomes in their own divisions.

- Justin Roerink, principal of the Hanover Center for Trades & Technology speculated that the trend might be found in a lot of classrooms. He queried, “How important is the material we are asking students to learn?” He further questioned the value of material we present to students if they don’t remember it a day, a week, or a month later. He encouraged increased use of hands-on assessments.

- Stephanie Haskins from Staunton City Schools, noted that for a long time teachers have been caught up in the details of what needs to be taught rather than the big ideas of, “what is the important concept here?” She suggested that now is a good time to back up and forget about “all the details and all the bullets” and focus on the big ideas we really want students to understand. These big ideas will be far more memorable.

Moderator John Ross shared an overview of a backwards design process, one that many educators hear about but few use in practice, at least according to his experience. In that process, prioritized standards lead to those big ideas Stephanie Haskins references. Then assessments are developed first, based on those big ideas, and prior to considering any instructional materials or activities. That’s the crux of backwards design: design the assessment first. Using a “Fist to Five” formative protocol, participants were asked “How does this backwards design process resonate with current practice in your division?” The most common responses were 2s and 3s.

- Stephen Castle from Hanover County acknowledged “4 in theory…2 or 3 in practice” further noting that it’s important to dedicate time to build a truly collaborative PLC structure where teachers can do the work of prioritizing standards and determining a systematic and structured approach to addressing them. He acknowledged that despite these efforts, some teachers may still be reluctant to trust that taking a mastery-based approach is going to yield the results they want on “the test” at the end of the year. He suggested many teachers pull back from more authentic instruction prior to testing and rely on “drill-and-kill” to get information pushed into students’ inert knowledge, which we know from Linda Darling-Hammond, doesn’t stick.

- Andrea Hand from Fairfax County Public Schools concurred with Castle and shared the idea of the tension between “have to have versus nice to have syndrome.” Some educators believe that one thing they “have to have” is good test scores at the end of the year, so they focus on that. Once they feel comfortable that will happen they can then work on the more authentic learning and others which, to them, fall under the category of “nice to have.” She suggests that the more we can advocate and align the “have to haves” with our collective beliefs around authentic learning it would guarantee students more of those experiences.

This tension is real, but many of the participants felt that our unique circumstances have given us reason to get back to what we know works to provide more authentic instruction that prioritizes learning outcomes to the needs of students, not just trying to cram in inert knowledge students will likely soon forget. Many of the participants continued through the rest of the week with additional sessions on designing performance-based tasks, creating learning progressions that lead to standards-based rubrics, and exploring portfolios and other resources to capture evidence of student learning.

Check out the conversation at this YouTube link, as well as the agenda with downloadable resources, a link to the slide deck, and links to resources from the other three sessions.