What if we designed high school experiences the way we design great instruction—by starting with the outcomes that matter most? That’s the mindset I brought to a recent project with Kennett Consolidated School District in Pennsylvania. As an instructional designer, I often apply backward design not just to instructional planning but to complex systems change. In this case, the goal was ambitious: redesign the high school experience to better prepare students for college, careers, and life.

This post offers a behind-the-scenes look at how we used scenario-based design to co-create a new vision for high school—one shaped by students, educators, and community partners. You’ll see how intentional design and facilitation helped clarify goals, surface student voice, and chart a path from vision to action.

Start with the end in mind.

The school district’s Office of Innovative Programs is building a unique program for their high school students called Kennett Future Ready. Its goal is to offer students authentic learning experiences through dual enrollment with a higher education institution and by earning industry-recognized credentials through work-based learning.

Seniors will complete an internship or a capstone project exploring a problem of practice or a community issue. Some initial pathways for work-based learning include computer science, engineering, and graphic design. Partnerships with local businesses and higher education institutions provide the backbone for these experiences and offer mentorship, internships, and flexible curriculum.

Design with community voice.

When I first joined the planning process, the energy was palpable. Everyone from district leaders to business partners had compelling ideas for what the program could do. But like many ambitious initiatives, we needed clarity: a way to define what the program should do. The project needed focus and clear goals.

My first step was to get input from all relevant parties: local business owners, teachers, school and district administrators, and, most importantly, students. Synthesizing and organizing the diverse perspectives helps program coordinators better understand a clear vision for the redesign project, but facilitating such a complex process does require a plan and strong facilitation skills. Leaders who want to launch a redesign project including diverse community input should carefully consider who has the right skill set and capacity to organize the process, facilitate the conversation, and synthesize the results to drive toward action.

Leverage a scenario-based design process.

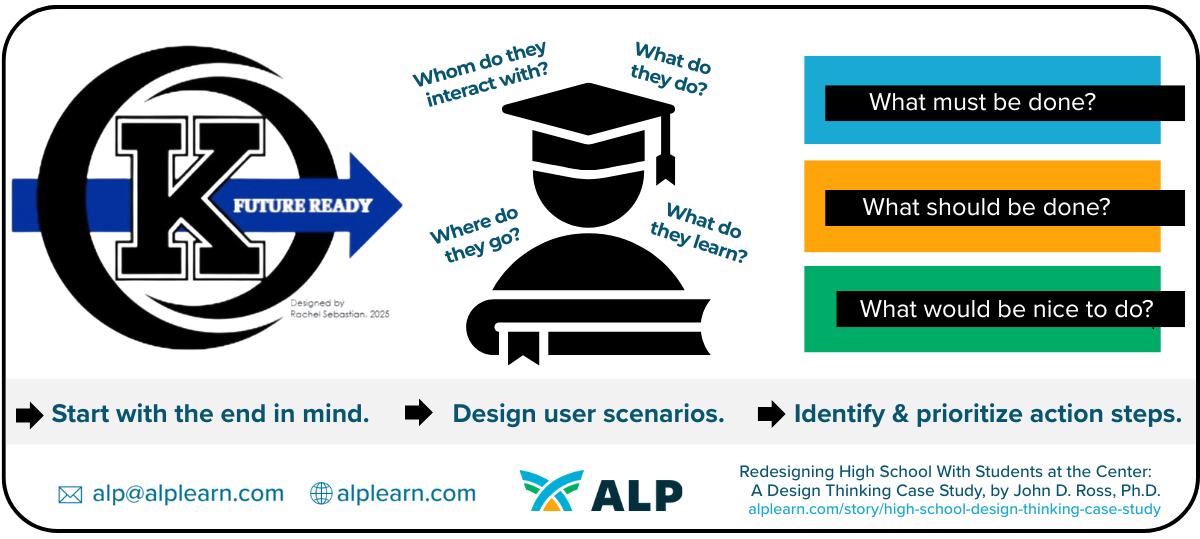

To help the team imagine their ideal outcomes for a redesigned high school experience, I facilitated a scenario-based design challenge. The Supervisor of Innovative Programs, Dean Ivory, organized participants into role-alike groups. Each group designed “A Day in the Life of a Kennett Future-Ready Student,” imagining the students three to five years in the future and describing their ideal day from morning to bedtime. I asked them to consider the following questions:

- Who were students interacting with?

- What were they learning and doing?

- Where were they learning?

- What tools, resources, and supports helped students succeed in their learning experiences?

This type of scenario-based design (SBD) has roots in Silicon Valley. IDEO used it when developing the first computer mouse. I learned about it many years ago through a graduate class with Dr. John Carroll, former Head of the Computer Science Department at Virginia Tech, and it’s been a staple in my instructional design toolkit ever since. The process is a subset of “human-centered design” and is similar to “design-thinking.”

Translate stories into strategy.

After sharing stories, we looked for themes. Reviewing stories requires qualitative analysis skills, and the richness of these stories goes deeper than a typical survey with checkbox options. Stories reveal priorities, hopes, and friction points. They create a vision that expands beyond a simple statement. Also, analyzing stories is fun!

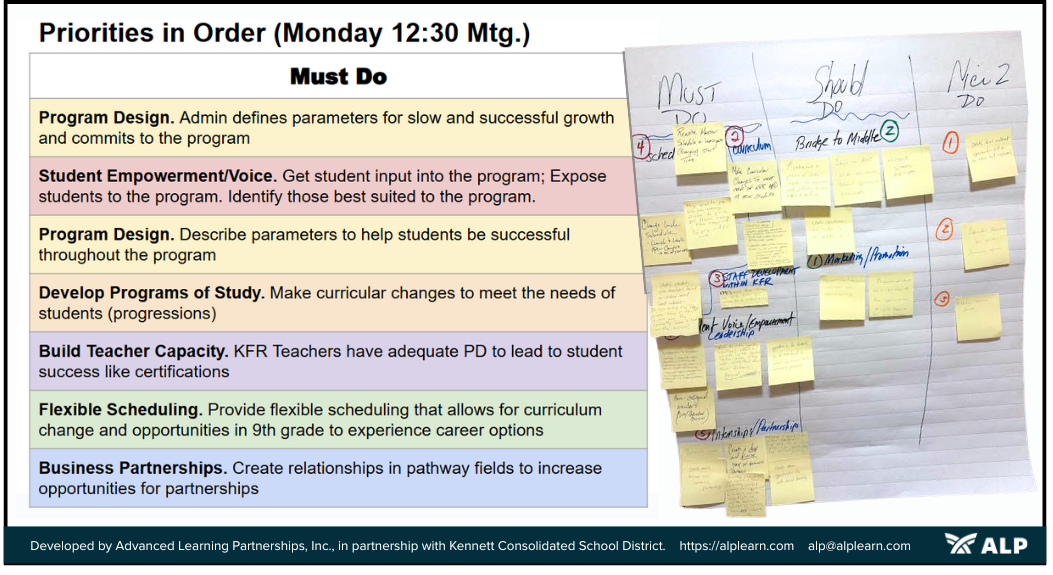

To move from vision to action, we sorted themes into three categories:

- Must do–non-negotiables for success

- Should-do: important elements that strengthen the program

- Nice to do: ideas worth exploring later

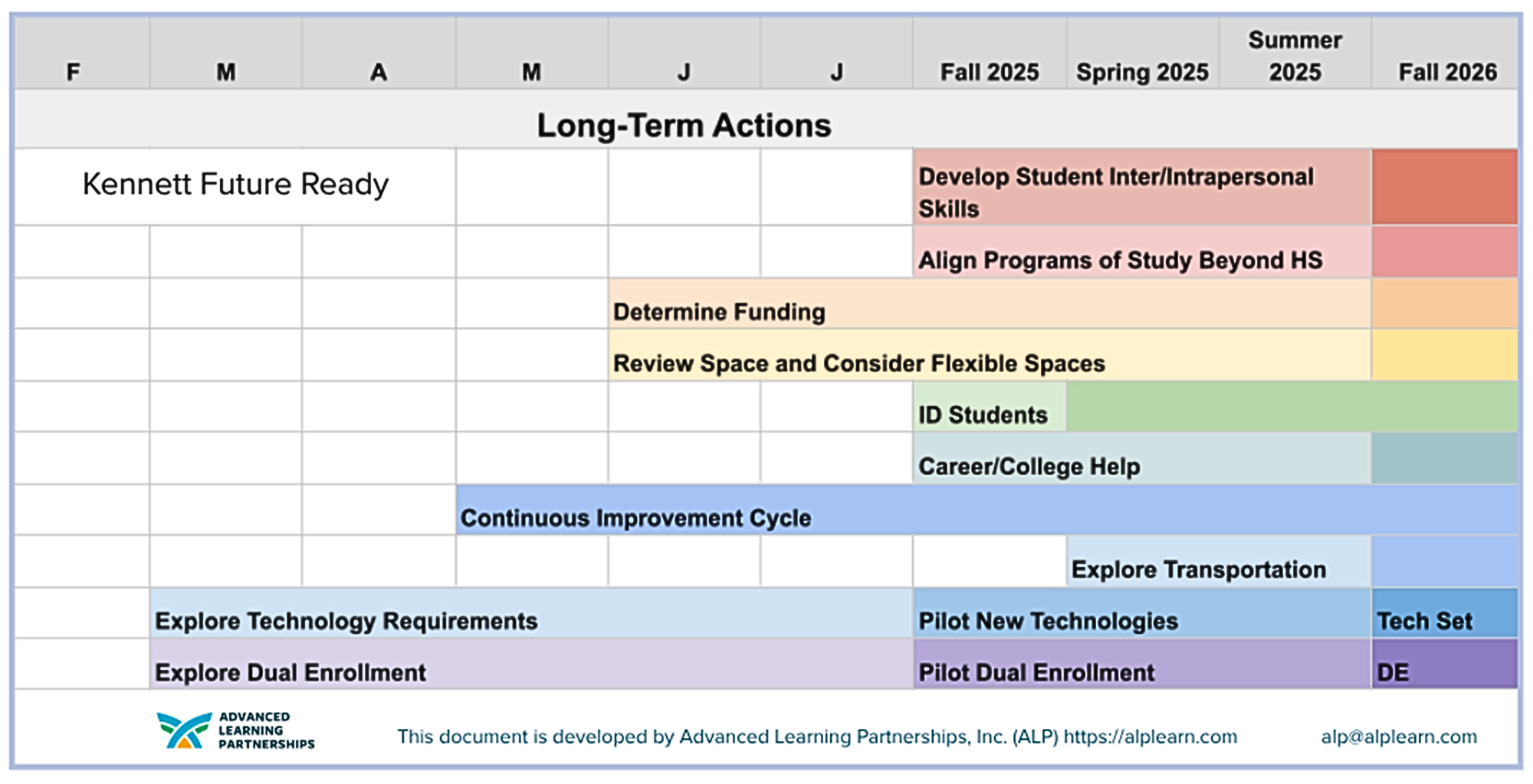

When time allows, we also prioritize within the “must” category to create urgency for immediate actions and a timeline for future ones. This sorting process makes people’s ideas tangible and these categories become the basis for a timeline with tangible action steps and benchmarks. In Kennett’s case, we were able to quickly generate a Gantt chart to help organize the goals over the next few years.

This story analysis process is adaptable. I have used it as a visioning exercise in school districts across the country for a diverse range of projects. No matter the context, it consistently surfaces insights that might otherwise go unspoken and transforms big ideas into shared direction. More than a planning tool, it’s a catalyst for clarity, alignment, and collective ownership.

Center student perspectives and ideas.

Students bring a fresh perspective, and Kennett’s student stories were especially telling. In my experience, they usually are. Despite the best of intentions, programs are often designed for students rather than with students, missing key insights like what would drive student interest in the program and what they want to get out of it.

Students often enjoy telling their stories and they regularly bring in elements we adult designers haven’t considered. For example, students made it clear that scheduling was one of the most important issues for them. They need flexible scheduling to accommodate classes, sports, clubs, hobbies, and family time, as well as the new work-based learning opportunities.

Student stories reminded us: programs work better when students help design them. Their input didn’t just validate our direction, it reshaped our priorities. Centering student voice in the design process helped us move forward with more confidence, clarity, and relevance.

Slow down to build a strong foundation.

As we synthesized feedback from all the stakeholders, the path forward became clear and a key insight emerged. We needed to slow down to build smart. Rather than rushing to launch, the team opted to pilot the program the following academic year. This allowed time to:

- recruit additional business partners

- develop clear documentation and processes

- prepare teachers and students

Luckily for Kennett, there was great student interest in the program, so a delayed launch wouldn’t derail excitement. Everyone seemed relieved and invigorated by a plan that matched ambition with strategy. After sharing our findings and recommendations with the Superintendent’s cabinet, the program received full support.

Co-Design with community and students.

With a strong foundation in place, the work continues. Dean Ivory leads the effort to clarify and document expectations for students, families, and partners. He and the students are working to recruit additional businesses to offer partnerships and pathways aligned to student interest. Input from the students and business leaders has been used to identify Key Performance Indicators (KPI) to measure the success of the program once it launches. Creating KPIs was possible because the visioning session and story analysis clarified the priorities of the program.

Student stakeholders have participated in a second design challenge: mapping their own senior-year experience. In the summer, Kennett students participate in summer internships, and planning is underway for the fall pilot. Long-term, the district aims to extend elements of Kennett Future Ready into earlier grades to prepare students for success in high school.

Designing with intention and with students is what makes high school redesign meaningful. At Kennett, that process began with stories and led to strategy. Soon, we’ll be able to compare real experiences to the “Day in the Life” visions that launched it all. And that’s when the next stage of learning begins.

Are you ready to redesign learning?

Kennett Consolidated School District leveraged key consulting support through a professional learning partnership with Dell Technologies and ALP. ALP offers several services to support schools, districts, and organizations to imagine, design, and innovate learning experiences for kids and adults. To learn more, check out another district case study Winchester Public Schools and read how ALP’s Sr Director of Partnerships describes how all education systems should be Rethinking High School. A team of Dell Education Strategists and ALP consultants designed another version of a Day in the Life to offer a vision for districts interested in high school redesign. ALP has been learning and iterating with education partners for over a decade to strengthen learning

If you want an experienced change management consultant and highly skilled facilitator to lead your visioning sessions, contact ALP for customized support.

Dr. John D. Ross has extensive experience supporting state and local education agencies in developing and implementing key initiatives, grounded in both research-based and emerging promising practices. As an instructional designer, he provides job-embedded coaching, collaborates on blended and performance-based learning, and helps districts nationwide establish student tech teams that enhance adult capacity while preparing students with real-world skills. John believes learning should be fun, relevant, and memorable—achieved through thoughtful, personalized design rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. Outside of education, he volunteers with a nonprofit arts center and was honored by NRV Leading Lights for his dedicated service. Follow John on LinkedIn.

Chat GPT was used to support the human-led editorial review process.